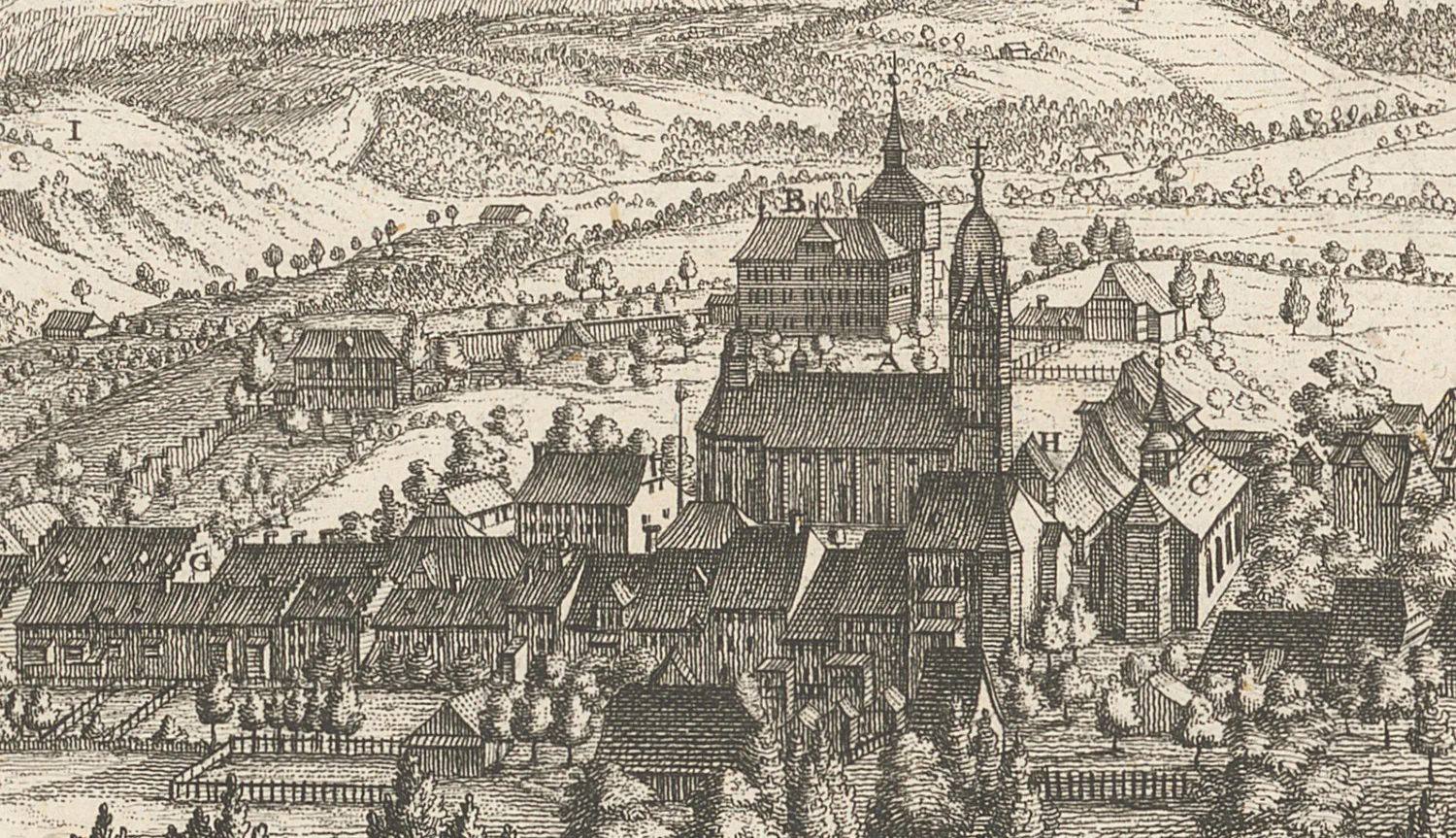

Willisau. A small town and open history book

Small towns are rich in cultural history, remnants of which leave their mark on the public space and shape our historical awareness. Willisau is no exception: a small town that wears its biography openly, with an enticing mix of the typical and the unusual that is both instructive and appealing.

The Lower Gate. A monument in the truest sense

The old hospital. Light and shade

Small-scale animal husbandry causing occasional trouble for the owners

The town hall – an erstwhile merchants’ hall and theatre

Gasthaus Adler. The façade paintings and their meaning

Street resurfacing and a source that can only be consulted once

The parish church. An elephant in the town centre

“Innocent little child”. An eternity without joy and sorrow

Living and working under the same roof 500 years ago

The miracle of the Holy Blood. How many stories does humankind need?

Moving with the times