Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, New York

Extreme pictures from extreme times

Two German painters, contemporaries, reacted to the ‘age of catastrophe’ of 1914-1945 in very different ways. One painted a harsh and objective depiction of the world he saw. The other persisted in a rural idyll. Both approaches are political.

There are phrases that promise a lot, but say very little without a bit of extra information. This includes the statement that pictures are a mirror of their time. Ultimately, that’s simply an instruction to go ‘back to square one’. The question to be asked is, which images of the fictive universe reflect what aspects of the period in question, with what intention and for what target audience?

In 1926, the painter George Grosz interpreted the supposedly golden age of the Roaring Twenties as an eclipse of the sun. For Adolf Wissel, the sun was still shining in 1939, and it was still shining on an ideal world. Grosz had to flee from Hitler’s henchmen as early as 1933. Wissel’s picture Kahlenberger Bauernfamilie (Farm family from Kahlenberg), on the other hand, ended up in Hitler’s Reich Chancellery.

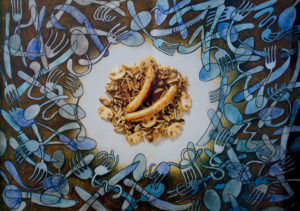

George Grosz, Sonnenfinsternis, 1926

Heckscher Museum of Art, Huntington, New York

The upright rectangular painting measures 218 x 188 cm. The expansive surface area is in itself a statement. And have you ever seen a picture with a table like that? Defiantly positioned at an angle, it stretches away to every side of the picture, dominating the painted surface, and even projecting slightly beyond the edge of the picture on the left. If a piece of furniture can be dynamic, it’s this table with its gaudy colours.

Sinister gathering, sinister ambience

The meeting’s chairman is unimposing, hard to make out. A mere placeholder, as the interlaced fingers also indicate: his hands are tied, and someone who has nothing to think and nothing to say doesn’t need papers and things to write with. The minute-taker beside him is supposed to be doing the writing. Only half of him is shown, but even that is actually too much. Finally, there are two other gnomish cardboard dummies, who are making a great effort to look as if they’re meant to be there, in line with the rules at any rate. All four of these men in tails are headless. The only straight thing about them is their stand-up collars.

The monstrous general has the only say. The laurel wreath he wears comes from Napoleon, who in turn inherited it from Caesar. Pinned to his breast are orders of merit galore, the usual circus of service medals – and he even has a ringmaster’s epaulettes. His fists are clenched, ready to pound on the table as necessary. However, the military giant is only a mouthpiece. He bellows his orders in line with whatever the man in the top hat and pince-nez whispers in his ear – a representative of heavy industry, as indicated by the locomotive, cannon, dagger and rifle he holds under his left arm. ‘Oh, the shark, babe, has such teeth, dear, And it shows them peeeearly white.’

And the people? They’re there, standing on the table as a donkey with blinkers, eating up the edicts issued by this government. Woe betide the animal if it leans too far over its manger or if someone yanks on the rope, with a fastening like a snake’s bite. Then it will come crashing down, and the donkey will fall under the table, into prison, where death and ruin await it. Escape is impossible, as one minister’s foot on the grille shows.

The surroundings too are apocalyptic. The sun is covered by a dollar sign. Above the metropolis, ‘Berlin Alexanderplatz’, planes dash across the sky. Parts of the city are in flames. Does Grosz already see World War II looming into view, as if he were Tiresias, the blind Greek prophet?

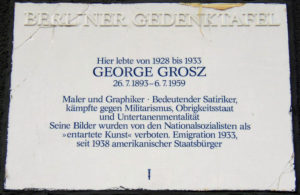

Commemorative plaque for George Grosz in Berlin-Wilmersdorf, Trautenaustrasse 12.

Wikimedia

A frank historical reckoning

The general appears to be a caricatured phantom, but he is not that, by any means. At the table sits Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934), President of the Reich since 1925 and successor to the social democrat Friedrich Ebert, who was driven to his death by backbiting nationalists. As a member of the Army High Command (Oberste Heeresleitung), Hindenburg was jointly responsible during World War I for the unrestricted submarine warfare that led to the United States’ entry into the war in 1917. He rejected a negotiated peace, and in 1918 forced Lenin to accept conditions for peace (Diktatfrieden). When the military situation nevertheless became hopeless for Germany, he requested an immediate cease-fire, because ‘Every day of delay costs thousands of brave soldiers their lives’.

No sooner had the Democrats agreed to the cease-fire – that is, lain down in the messy bed the empire had made for itself – than Hindenburg claimed the complete opposite: the German army was ‘undefeated in the field’, but had been ‘stabbed in the back’ by the incompetent government and by socialist and pacifist forces.

In his picture, George Grosz puts the ‘stab in the back legend’ on scathing public display. In the centre of the table lies an oversized dagger, smeared with blood, directly in front of the author of the lie, Hindenburg. Immediately next to it stands a small cross in the colours black, white and red. These are the colours of the old monarchy, which was abolished in 1918. The German Republic, with its black, red and gold colours, has no place at this table.

From one extreme to the other

Are we still in the same country, in the same era, with the picture below, Kahlenberger Bauernfamilie? The 150 x 200 cm painting by Adolf Wissel (1894-1973) dates from 1939. The previous year, 1938, huge numbers of Jewish shops were destroyed and set on fire on ‘Reichskristallnacht’, the ‘Night of Broken Glass’. The fire brigade did not attend the fires – imperial government orders! Jewish property was soon on sale at knockdown prices. This further silenced protests against the government-sanctioned night of pogroms.

The same year, 1938, marked the transition from Hitler’s tokenistic, dovish foreign policy to an openly violent one. The annexation of Austria was followed by the Sudeten crisis and the occupation of Czechoslovakia. On 1 September 1939, when the German Wehrmacht invaded Poland, reportedly ‘shots were fired back and bomb repaid with bomb’. That’s the time period in which Adolf Wissel painted his Kahlenberg idyll. He had been working on this picture since 1937.

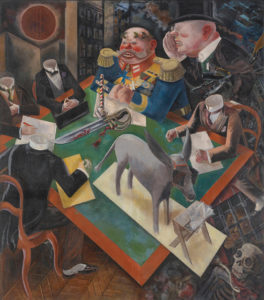

Adolf Wissel, Kahlenberger Bauernfamilie (Farm Family from Kahlenberg), 1939

German Historical Museum, Berlin

An inter-generational covenant in extreme times: grandmother, father, little boy – past, present, future. The grandmother is clearly on the periphery; her son is not in the centre either, even though he overtops everyone else. The focus is on the boy, the only one who is looking directly at the viewer. It’s clear who will someday be in charge.

The other group of three is also revealing. The older girl on the left of the picture, the mother and the younger girl on her lap are all lost in their own little worlds. The mother’s hands are folded as if in prayer. Her arms lovingly encircle her daughter in an embrace that is more than just tender protection. It also defines the boundaries of her life. Nothing will be any different for the daughter.

A doll is a portent of the girls’ future role as mothers, but it lies forgotten in a corner; it seems strangely inanimate, as if dead. The boy’s toy, on the other hand, a lively, prancing white horse, takes centre stage. Forward motion is palpable. Will the boy have no limits set for him in the future, either in the fields or on the field? – Strange, this curved horizon, as if it were the orb of our planet.

Even apolitical is political

‘With the right instinct,’ announced Berlin in 1941, ‘artists seek out their models primarily among the common country folk, who are still virtually uncontaminated, as nature intended; they look where closeness to the native soil, the nurturing vigour of rural life, the safeguarding of the blood against commingling, the power of long-established tradition and the benediction of charitable works have kept the substance healthy.’ True Nazi thinking. At the Great German Art Exhibition, the official annual Nazi art show held in Munich, 25% of the pictures on show depicted peasants, even though the proportion of peasants was only 10%. Manual workers made up 46% of the population, but their share in the pictures was a mere 0.7%.

Research on Nazi painting describes Wissel’s painting as a ‘prototype of the ideologically conformant family image’. Understandable. The fact that Adolf Hitler bought the picture for 12,000 Reichsmarks would appear to support this classification. Other specialists note that Wissel drastically changed neither his style nor his subject matter after 1933 – so he didn’t adapt. Moreover, he ranked only in the second tier in the Nazi cultural and educational policy, including in key exhibitions during those years.

But the question still arises: the quintessential Nazi family portrait? Considered in the clear light of day, other facets become apparent. What happens when a painter has dedicated himself to the genre of farming and rural motifs, if that is exactly what the Nazi dictatorship now officially demands? And why do the grandmother and her son in particular look so oddly serious, perplexed, almost distressed? Ultimately, is this family lamenting some calamitous blow of fate – or contemplating an ill-omened future? On the eve of World War II, a heroic departure with flying colours would look different, anyway.

To the end of his life, Wissel described himself as an apolitical painter. To what extent was he, as one who was a beneficiary of it, also a participant in the unjust Nazi regime? Could artists who were in the public eye at that time simply ‘pursue their vocation’? Mirrors never lie. It’s a law of nature. But one has to be aware of what one is holding up to the mirror. Grosz or Wissel – that’s the difference.

P.S. The atlantic swimmers

Wissel’s looking the other way, Hindenburg’s misrepresentations, Hitler’s lie: nothing more could be done. And how do we counter the lies of democratically elected presidents of our own times? Herbert Achternbusch advised the Atlantic Swimmers: ‘You don’t stand a chance, but use it.’