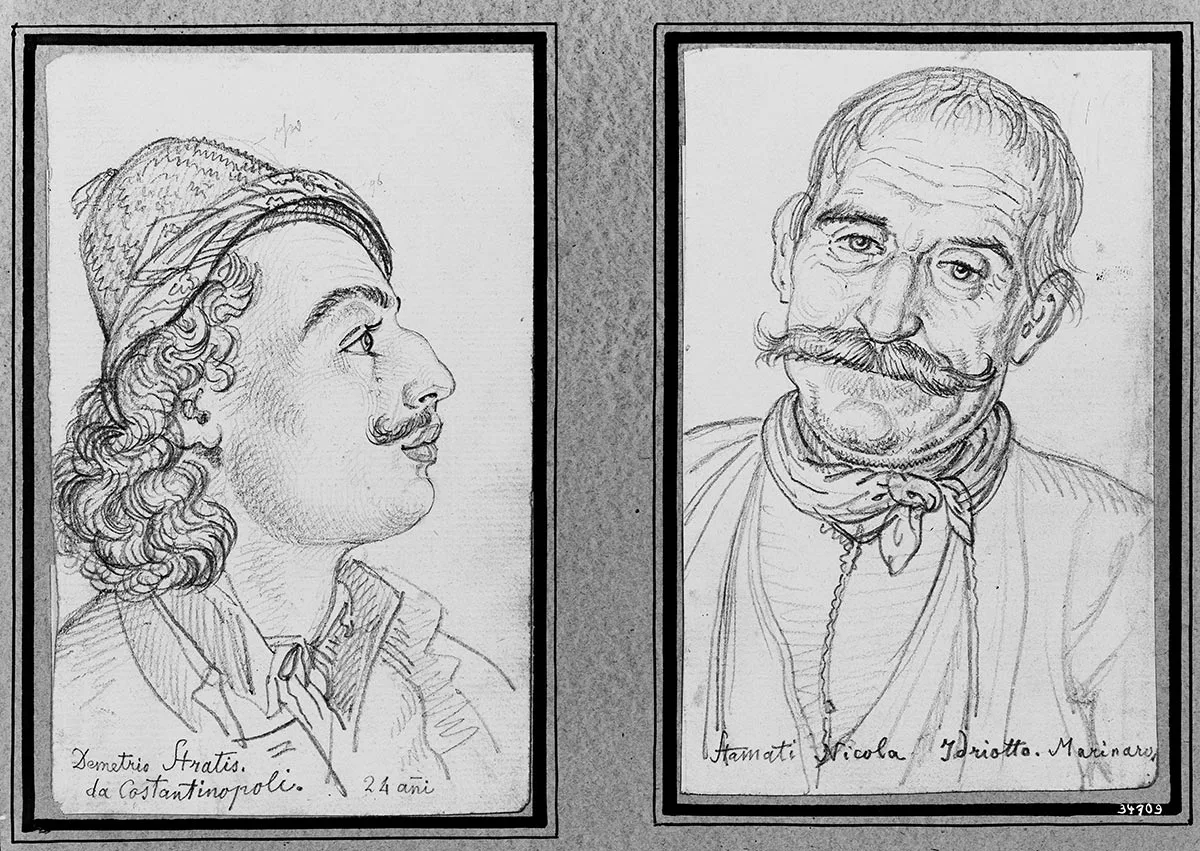

The odyssey of the Greek freedom fighters

In 1823 around 160 Greek revolutionaries ended up in Switzerland, having been defeated and persecuted by the Ottomans. They escaped on foot on a route that took them via Odessa, Bessarabia, Poland and through German states to the border in Schaffhausen.

The secret Filiki Eteria society plans an uprising

Devastating defeat and flight to Odessa

Marching from Odessa to Switzerland

Intervention by major powers and liberation